Woodturning Tool Revolution

During the past 30 years there has been a revolution in the development of wood turning tools, namely bowl gouges, lathes, fixtures and techniques. What was deemed impossible to turn a few years ago, has become common place today. And the creation and invention continues. Most of the development stemmed from new design ideas; where conventional tools could not be used to implement them. To progress, it is sometimes necessary to create a new conventional wisdom to implement your ideas. “If there is one given it is this: you can 't wait for technology. You must create it, if you want to accomplish your goals. You can not allow your imagination or your creativity to become stifled by present day knowledge or conventional wisdom. Create the necessary technology, tools, and develop a new wisdom to reach your goals.” Howard Lewin, “Artist’s Statement” 1990

What this article is going to talk about is this fantastic growth in wood turning tools. It is taken from a personal perspective, in that I have been a part of it for the past 30 years. No doubt there will be omissions, but I am not trying to write an historical dissertation on the subject, rather more of a synopsis of what has occurred.

When I began turning in Junior High School, using gouges to turn bowls was not an option. It could not be done. Like all woodworking novices and journeymen alike I believed this to be sacrosanct and beyond discussion, and for years I scraped my way through wood to turn a bowl. It took a long time and required a lot of sanding to complete a bowl. The tools available were usually manufactured by bucks brothers. They featured short handles for both the spindle gouges and the bowl scrapers, and the steel would not hold an edge. It is a fact that the ceilings above most school lathes had holes or dents in them from flying tools . And then.....

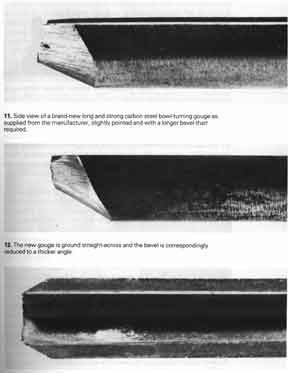

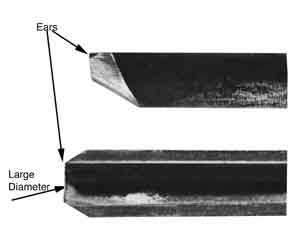

In the early 70’s an Englishman, Peter Child wrote a book, The Craftsman Wood Turner. The major premise of this book was that bowl gouges could and should be used for turning bowls. He had developed the “Long and Strong Bowl Gouge” and Sorby England manufactured it. It was an unheard of concept: turning a bowl with a gouge. After reading the book, I purchased one of the gouges, and my what a difference. What took hours of scraping was reduced to minutes with the gouge. This gouge of his had one really severe drawback. It was square faced with ears or corner points that tended to catch the wood, especially near the edge of a bowl nearing completion. Another problem was the tool’s large arc ie the bottom if the “U” which, if not held very firmly, tended to skate across the bowl blank’s surface. A third problem was that the handle was to short, even though it was longer than conventional tools. Additionally, the tool’s steel was high carbon, which obtained a sharp edge but could not hold it for long. In spite of these problems, it was the best tool available at the time and it made bowl turning easier and faster.

He had also developed a set of scraping tools, that were used specifically for the transitions inside and outside the bowl and to smooth out the ridges left by the gouge. These scrapers were very heavy and long handled. They too were of a radically different design than conventional scrapers. Because of their mass and long handles, they were much easier to control. However, they too were made of high carbon steel, and dulled rapidly.

In addition to the bowl gouges and scrapers, Child introduced us to a new kind of spindle gouge, heavier steel and longer handles, with the emphasis on cutting and slicing rather that scraping the spindle. Most American turners scraped spindles, which made for heavy sanding and lost detail in that process.

By the late 70’s, certainly no later than the early 80’s the Child’s “Long and Strong” gouge had been modified by most of the English turners. They began by grinding off the pointed tip(the ears) of the flat face. They ground it way way back, giving it much longer cutting surface. Most of the turners added a much longer handle as well which gave them greater leverage and control. My first encounter with this gouge style was in 1984, and the turner was Liam O’Neil. What that gouge allowed him to do simply astounded me and all of the other turners at that demonstration. An American turner, David Ellsworth, had begun using and teaching the use of that English grind a few years earlier. By this time, Sorbys and Henry Taylor, both manufacturers from England, had practically locked up the gouge market. They were the sole source for the Child’s style gouge, and the modified English Grind.

In the meantime here in the United States, Bob Stocksdale had modified a Marples bowl gouge that he had used exclusively since the he began turning in the early 40’s. His use of the gouge predates, to the best of my knowledge, any other turner. When Bob met Jerry Glaser in the early 60’s they set out to improve that gouge. The evolution of that tool, the Stocksdale gouge, has led to a whole family of both spindle and bowl turning gouges. Additionally, articulated boring bars, screw chucks and sharpening devices were developed to fulfill the requirements of a new generation of woodturners.

The deeper fluted gouges of Jerry’s design and their longer handles made bowl turning easier, faster and safer. In the mid-eighties, with some misgivings, Jerry changed his handles to aluminum. These hex shaped handles withstood the shock of turning, practically eliminating the possibility of breaking but more importantly, for me at least, they did not tend to roll off of a workbench. The most innovative aspect of the aluminum handles was that they could be hollowed out and filled with buck shot. This concept made the tool practically vibration free, and the added mass gave it much more stability. What happens is this: the vibration that is generated at the tip of the tool when it is cutting is transferred down the length of the tool where it is again transferred to the buck shot. Since the buck shot is not packed tightly, it begins to resonate. If you could x-ray the handle, while turning a bowl blank, there you would see some nifty buckshot gyrations. Jerry also changed the tool steel. He had been experimenting with M2, M4, and settled on a steel that he called A11. It maintains its edge 5 times longer than any of the others. This too has changed again to CPM15V. The evolution of these tools have now placed them as the choice for most professional and amateur turners.

In addition to these fantastic bowl gouges Jerry made several advances in the design of spindle tools. His round nosed scraper which I grind way back and call a round nosed skew, when equipped with an aluminum handle filled with buck shot, gives a skew like finish to the wood, and can be used to cut coves, beads, and plane long straights. It is the only spindle turning tool you need.

In the seventies, David Ellsworth began turning hollow vessels. His first tools were scrapers that he had bent with a welding torch. These tools were somewhat limiting, and he later began to use machinist’s boring bars that had a permanent set of 45 degrees or straight. The development continued and longer handled tools with swivel tips that held machinist’s tool steel were made, these not only gave more control, and allowed greater flexibility of design, they were safer as well. These early swivel long steel bar tools were made by Jim Thompson a woodturner from North Carolina.

Things seemed to slow down for a bit, until Dan Kvitka gave a work shop in my studio about 1987. One of the attendees was Jerry Glaser. We asked him if he could design and build a small boring bar with a swivel tip which would allow us a greater angle of attack through the small openings of hollow vessels. Jerry got to work, and several prototypes later came up with a double articulated swivel, an attached counter weight to the boring bar, which really dampened the tool’s tendency to jerk your wrist, and a buck shot filled handle. This double articulation allowed making heavy cuts because the geometry of the swivels reduced the tool’s tendency to grab. With affection, I dubbed this tool the oozie. This made turning hollow vessel style pieces up to 12” much easier and safer. Jerry also started making the same double articulated swivels on a square tubular steel bar 5, 6 and even 7 feet long filled with buckshot for really deep hollow vessels. With these longer tools it is possible to hollow turn vases 30” deep.

Somewhat earlier, early 70’s, Edward Moulthrope began turning very large hollow vessels, 30” diameters and 36” tall. These turnings required special tools. Mostly hooks and eyes welded on very long steel bars. This innovation allowed him to hollow turn very large pieces through a relatively small entry hole. The difficulty was cleaning out the shavings. They would compact so tightly that trying to force a cut through them usually caused a problem. The lathe he designed was humongous.

At another workshop at my studio, Dennis Stewert introduced us to a tool that he had developed. This was around 1986. It was a round steel bar that had a carbide saw tooth welded to its tip and was bent at about 30 degrees for a round handle. I remember turning the handles to complete the tool. Dennis used this tool to slice into wood for coring and making small thin walled vases. This concept later developed into a much longer and stronger tool with an arm attachment, a hooked tip for turning hollow vessels, and a better coring cutter. Later versions incorporated additional features . I believe that it is now manufactured by Sorbys.

On a high ridge in the back hills of central Kentucky, near the town of Berea, before time began, Rude Osolnik developed a spindle and bowl gouge ground out of a single flat bar of steel, a tang was shaped, and a long handle attached. It was a workable tool and very inexpensive to make. Rumor has it that Rude traded a “spalted” log for a box of 3/8” flat tool steel bars. From these he fashioned his tools . These tools then became affectionately known as the “poverty ridge” brand. When Rude ran out of that original box of tool steel Ernie Conover was persuaded to manufacture them for awhile, probably because Rude had run out of “spalted” logs to trade.

Along with this incredible growth in cutting tools there were tremendous advances in chucks. 3 Jaw chucks, 4 jaw chucks, scroll 4 jaw, expansion chucks, collet chucks and screw chucks. The advantages of these scrolling or self-centering chucks was that wood was automatically centered in the chuck. This self-centering feature was also an advantage because it facilitated the mounting of a piece on the lathe. Perhaps more importantly, especially with the four jaw chucks, an additional jaw made holding the work much more secure. This secure attachment to the lathe makes possibile a whole new approach to turning projects.

Perhaps the most important development of all was in the creation of slow speed lathes for bowl work. The early lathes were developed expressly for spindle turning, and “could” be used for small diameter bowl turning. Speed on most lathes began at 1000 rpm. Even a small diameter bowl could become a lethal projectile. With the advent of moderately priced DC controllers in the late 70’s it became possible to reduce lathe speeds and give turners better control of rpm. It did not, however give them the necessary torque. To increase torque a system of jack shafts were used. By the mid 90’s frequency controlled moters had given the turner both speed control and enough torque to accomplish just about any creation one could imagine. And all of it in the head stock without the encumbrance of exterior belts and pulleys. The latest machines have much more mass which reduces vibration, and allows for the safe turning of very large pieces.

Sharpening has always been difficult. Most grinders are driven by motors with 3400 rpm, and gray wheels are used. The wheels are great for grinding metal but not for sharpening. They do not exfoliate, and therefore generate a great deal of heat bluing the steel. Slow speed grinders with white aluminium oxide wheels allow sharpening without the risk of bluing the edge, ie taking its temper out, the bane of most woodturners. It does this by exfoliation, losing a part of itself, creating new sharp facets of stone to the steel.

What all of this is leading to of course is the fantastic artistic explosion that these new tools have made possible. Hollow vases, spirals, offset turnings, multi centered turnings, turnings with bark inclusions and voids in the sides, lidded boxes, translucent flowers, cowboy hats and on and on. Because sharp tools allow cutting thinner, with less effort, less sanding, less fatigue and fewer accidents, more and more woodworkers are becoming involved in wood turning. And consequently the more varied and interesting the work coming off today's lathes.