Review by Earl Young-USAID Area Coordinator Vientiane Province/Director USAID Burma

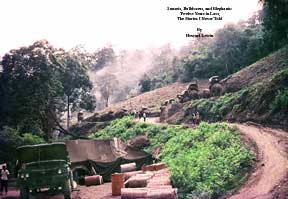

"From the eye-catching photograph that draws the reader's attention

to the book cover, through his very personalized account of adventures that

spanning twelve years in the unbelievable Land Of Nod, aka "The Royal Kingdom

Of Laos", Howard Lewin has turned out a fine first effort.

Either deliberately, or by great good luck, he has chosen to

give an intimate, day-by-day account, warts included, of his service, first

with the American International Voluntary Service team and then as a member

of the U.S. Agency for International Development. He has retained most of

the details and the book often reads like a diary, as he frankly discusses

his successes and problems.

He breaks new ground here, detailing the day by day life of

an ordinary civilian trying to accomplish meaningful tasks in a war-ravaged

country, The more popular route would have been the usual expose of CIA activities

in Laos, the bombing campaign by the U.S. Air Force or the swash-buckling

activities of Air America pilots. But the plentiful supply of good photographs

that accompany his story of everyday life make even clearing a road through

the jungle clear even to non-engineers.

The book will appeal most of all to the "Old Hands" who served

in Laos, and undoubtedly raise the blood pressure among many....But, as Mr.

Lewin writes in the dedication, his story— elephants, bulldozers and

romantic interludes included— is something he wanted his children to

know. They can be proud of their father..."

Review by Chris Russell-USAID Area Coordinator Luang Prabang and Pakse

Several days ago I received your book and sent off a letter

to you expressing my conviction that your memoirs are the best yet written

about the period in which some of us served for varying lengths of time in

Laos. Congratulations, Howie! Your revision of the original manuscript is

a great success and the final, like the original, is fascinating, insightful,

entertaining and wonderfully lively.

Review by Jack Kurek

I started reading your book the day I received it. Knowing you after you returned from Laos, and remembering some of your comments and

discussion when I met Gus, I must say -- What an adventure. Certainly the other side (perhaps the real side) of Howard.

On the one hand, it must have been very rewarding when looking at your accomplishments in Laos, and the improvements you made to lives of

many. And on the other hand, it must have been, and you did say it in the book, a real let down and disappointment when almost everything you did,

was compromised by the US administration and its involvement in the VietNam affair.

I know that I was amazed that you survived the many close calls that you had while you were there. And, your "stick to it'ness" must be

commended.

As you said, the experience was one that will always be remembered. Hopefully the good will remain, and over time, the bad will fade away.

From the book, it was a bit hard for me to understand how "close" you and Gus were. But, I do know from meeting him the day I went up to his

house, and then again when we were all at Woodcraft for your class, that you were good, close friends. So, I know the sadness you must have felt

when he passed.

The book was great. I saw a bit of history that otherwise I would never have seen. I appreciate that you took the time, the energy, and perhaps

the pain you went through, to relive those times which allowed a lot of your friends and other to share those times with you. One thing for sure,

the world would be a better place if the US used the dollars it wastes making wars and took that money and used it to improve the lives of

people that wanted the help.

Once I get back home for a while and can collect my thoughts, I will look up your book on Amazon, and put in a review.

Thanks again for sharing what I consider the insight into a significant part of your life. You certainly are on the top of my list of people to visit when I

next get out to the LA area.

Jack

Review by John S. Burton-Author Of "Lao Close Encounters."

Howard,

I have just recently found your book while searching IVS websites, bought it, and have read every word with interest. I’m an “old” entomologist and Peace Corps Volunteer who served at the headquarters of the National Malaria Eradication Project, which got me all over Thailand from 1965-67; and in 1969 I returned to collect flies all over the country for my final thesis. I used to cross the Mekong for a few hours whenever I was in a border province, which was at that time done just with the wave of the hand by police on both sides. So a lot of what you went through, I was also going through in Thailand, with several enormous exceptions: I didn’t have to worry about the war directly; I wasn’t in charge of materials; I never carried a weapon; and I was already married when I got there (still am, to the same remarkable woman). So of course our experiences, even though partly simultaneous, are just not comparable at the same level. Still, I thought you might appreciate a comment or two, so here goes.

You have succeeded handsomely in capturing the flavor of so many things that we went through: the idealism driving the founders of IVS and Peace Corps, and we who signed up for them; the desirability of maintaining those ideals; the innocents abroad phase (euthanasia, pardon the pun); the importance of listening to the folks in the field on the part of the policymakers; the everyday hazards of life in rural Southeast Asia; the difficulty of getting things accomplished; the role of local beliefs, including fate; the dubiousness of press reports; and the change in attitude of those who came from the USA to replace us. And, yes, we took in all the peripheral stuff too: the A&W in Kuala Lumpur (knew it well); Taal Volcano in S. Luzon; the Raffles; the squalor of Jakarta; and the extravagant Siam Intercontinental (now being replaced by a skyscraper). And of course the reverse culture shock of returning to the USA (in our case after 33 years overseas). I note that your copyright page shows “First Edition,” implying that there might be a second. I will only share with you a proof reader’s critique if and when you tell me there actually will be a second edition, and then only if asked.

I watched for names that I might recognize, and only saw one for sure: Val Peterson, who I met in Luang Prabang in August 1969. And is Earl Young a brother of Gordon, and son of a former director of the Chiang Mai Zoo? I know at least five other folks serving in Lao at the same time you were, but they were not mentioned.

This leads up to telling you that we lived in Laos from 2001-2004, and I managed to set foot in every one of the currently delimited 141 districts. I didn’t set out to write a book, but like you, I did so anyway—I just didn’t wait for 29 years before doing it! Mine is a book describing Laos today in 1200 color photos. I could have called it “Lao Now” if I had wanted to be flippant, but eventually landed on “Lao Close Encounters.” It is just now becoming available in North America for purchase on the internet at Antique Collectors Club or at Amazon.com Based on my reading of your book, I think I can safely say that you would find it interesting.

Your website makes it clear that you are a highly accomplished artisan in wood. We greatly admire such talent.

With best regards,

John J.S. Burton

Introduction

In the fifties and early sixties, the United States was embarking

on a serious commitment in Indochina. We feared the "Domino Effect": that

all of Southeast Asia would eventually come under communist rule. The communist

insurrection in Malaya, 1948-1960, successfully countered by the British,

was an example of what we feared for all of Indochina. The difficulty of that

exorcism and the deep anxiety it produced eventually pushed us reluctantly

to the brink. These mounting concerns convinced us of our need to get involved

in the Vietnam War.

In addition, many key policy makers believed that we needed

French backing against communism, especially in Europe. This requirement for

French support dragged us even deeper into the quagmire of Indochina. One

of the conditions for their assistance against European Communism was that

we back them in their attempt to regain control of their colonial empire in

Indochina, both militarily and economically. The French troops that landed

in Hanoi shortly after the war were equipped with American weapons, ferried

ashore on American landing craft, and supported by the American navy. All

this was done in spite of Franklin D. Roosevelt's promise to give independence

to colonial dependencies — hollow promises given to gain their assistance

against the Japanese. This myopia in distinguishing between the emerging nationalism

of the colonials and hegemonic communism was the root cause of our eventual

involvement in Indochina.

In spite of our ill-advised willingness to help the French

retake their colonial empire, they threatened numerous times to become neutral

in our fight against European communism, and we fell for their false promises

of support. Each time it cost us more in terms of the economic development,

and reconstruction of post-war France.

In the early sixties, the United States Agency for International

Development (USAID) began a project in Laos called the "village cluster program."

They contracted with the International Voluntary Services, Inc. (IVS), to

provide staffing for this program. IVS was a natural choice because it already

had volunteers "in-country," working on a variety of self-help projects,

trained in the Lao language, and sensitive to the Lao culture. These early

recruits were mostly technical people proficient in agriculture, engineering,

animal husbandry, and teaching —all skills needed in a developing country.

The fact that a war was going on, not only in the military sense

but for the "hearts and minds of the people" as well, made the enterprise

all the more challenging. For those of us who made the journey, we learned

what we were capable of, living in an environment that at times was hostile,

not just in the military sense, but also in the natural sense as well. I never

knew how many dangerous diseases there were. I never knew what hot was until

I went to Laos. I never knew that mosquitoes could be so voracious. Sure,

I had been bitten by mosquitoes, but never carried away by them to be sucked

dry. I never knew just how lucky I was to be an American.

All of this I learned and much, much more.

Preface

Everything you are about to read actually happened. These events

have been etched in my mind and are only snapshots, much like the image reflected

by a flashlight beam piercing a dark room. Unfortunately, it is a flashlight

beam that is blinking on and off and powered by weak batteries. It is not

complete, only an image, a part of the whole. I have tried to keep the chronological

order of events, but probably, through error caused by the long lapse of time,

I have not succeeded completely. I was worried about this at first but feel

that the telling is more important than the sequence in which the events occurred.

Some events have been "elaborated" upon to help explain or to disguise the

actual characters involved. All mistakes, of course, are mine. Opinions expressed

are mine; however, many are shared by others who have had similar experiences.

All I wanted to do after returning home in the spring of 1975,

after twelve years in Laos, was to forget, bury what I had seen and done,

and begin a new life. I was angry, bitter, and just wanted to get on with

the rest of my life. For a while, I thought I had succeeded, but disturbing

dreams began to creep into my sleep, and several "flashbacks" jarred the memory

of certain events into the present, memories I thought long since forgotten.

I could no longer ignore what was happening. It was time to deal with my experiences.

When I first came home, every attempt to explain my experiences

and duties in Laos was met with a quiet disdain. I could see in the faces

of friends and associates a gradual distancing, anxious looks of distress,

a glazing over of the eyes. It took me a long time to realize why. It was

way beyond their ken, beyond their experience to understand. The folks at

home had been bombarded with half-truths about the events in Vietnam, Cambodia,

and Laos. Anyone associated with those events was not given a chance to elaborate.

GIs returning from Vietnam experienced the same reaction, only much more negatively.

This is a story of my experiences, what I did, what I accomplished,

how I failed, and what I learned. It is the story of how I went from a master's

degree in history to a reasonably competent but not so civil civil engineer.

It is also a story about men and women who performed daring deeds, and about

people who pushed to the limits their physical, mental, and survival instincts.

It is about people who served their country with great distinction. Let there

be no mistake on this, most of the people who went to Laos were dedicated,

hard-working, intelligent people. Anyone who lived and worked in rural Laos

during this time has a similar story to tell. In a way this is their story

too.

It is difficult for anyone who was not present in Laos to understand

the significance of the events that took place, both on a personal level and

as a part of the whole picture of the Vietnam War. It is even difficult for

me to grasp, though I was "in-country" for twelve years. I was never involved

in the "upstairs" planning. My tasks were of a more mundane variety. The whole

program in Laos was a kind of sideshow to the war effort, and often policies

were determined and carried out in Laos on the basis of what was happening

and thought to be needed in support of Vietnam.

You name it and Laos needed it. Roads, bridges, schools, hospitals,

irrigation systems, water diversion dams, power plants, hydro-electric dams,

water purification systems, sewer systems—the list is endless. We were

able to make some headway toward the completion of these much-needed construction

projects, but the war hindered our efforts and sometimes prevented the implementation

of many of them. What surprises me is that we were able to get as much done

as we did. This effort required taking some risks. Those of us in the Public

Works Division (PWD) who worked in the field faced the threat of enemy action

regularly. It seems that almost everything we built was programmed for insecure

areas. We were not alone in this. Others faced similar dangers trying to feed

and relocate refugees displaced by the war. Still others were placed in harm's

way during their attempts to encourage local officials to create programs

that instilled trust from their constituents and from their government. All

were very brave people and deserve recognition from their government and its

citizens.

We were lucky. No American PWD employees were killed or taken

prisoner. There were, however, many attempts and several close calls. We did

lose many of our Lao staff in construction-related accidents, and several

were taken prisoner but released after a relatively short time. There were

additional casualties from airplane crashes. Many of those casualties were

technicians under my supervision.

Prologue

The Public Works Division (PWD) had just completed an airfield

at site 36 (Na Khang). Months earlier, I had accompanied the first piece of

equipment into the place on a Caribou, a medium-sized, short takeoff and landing,

cargo plane. We made a greasy, wet landing on the rough airfield. Laotian

clay is greasy when wet. The piece of equipment was an engine from an HD-6

bulldozer we had disassembled at Moung Soui to fly into site 36 a part at

a time. While we were unloading it, the engine started sliding down the ramp

on its own and fell over, breaking the exhaust manifold. I was on a flight

that evening with the broken part, had it welded early the next morning, and

returned to Na Khang with the repaired part so that the re-assembly of the

dozer could commence.

My trip to site 36 this time was to cut or blast down some

trees off a ridge at the end of the runway. The pilots of C-123s complained

of scraping the hulls of their cargo planes on the tops of these tall trees.

I landed there with a crew of men prepared to spend as long

as it took to take them down. We headed up to the ridge carrying our gear,

made camp, and started to work. It was about three kilometers away from the

field, and from this ridge we looked down into the valley as though seated

on the top row of a very large amphitheater. We had chain saws for the smaller

trees and dynamite and C-4 plastic explosive for the larger ones. By 3 p.m.

we had made a substantial dent in the grove. With all of the racket we were

making, we didn't at first hear the noise coming from the airfield. But gradually

it became clear that something serious was going on. When we finally looked

that way, we saw that the airfield was under attack. In fact, some of the

rounds were hitting the very trees we were trying to cut down. From our vantage

point, we could see everything. I ordered all of my men to cease work and

keep their heads down. There were a lot of rocks there to take cover behind.

It looked like it was going to be a very long night because it was already

late afternoon.

The main fortifications were on a hill located adjacent to

the airfield. Across the airfield, the rice paddies (now dry since it was

well into the dry season and the rice had long since been harvested) were

covered by a force of Vietminh soldiers moving toward the entrenchments. The

defending troops were outnumbered ten to one. This was, after all, a guerrilla

outpost. My thoughts raced. Where are we going to go if the enemy attack succeeds?...

Site 36 was surrounded by mountainous terrain and the enemy controlled most

of the territory. The defenders were doing a good job, and the enemy, attacking

over open fields, was paying a heavy price. But they just kept coming.

When it appeared they were about to break through, we heard

a very loud roar, and a flight of "fast movers" came from out of nowhere to

drop a load of napalm on the advancing Vietminh. The valley was transformed

into a sheet of flame and the attack was over in that instant. The scene was

one of indescribable horror. The burning rice fields were covered with enemy

dead. Enemy troops not killed by the napalm attack were fleeing back into

the surrounding forest and hills.

Numbed by what I had just seen, all I could do was just stare.

My brain and body seemed to be somehow disconnected. Finally, I recovered

somewhat and ordered my men to pack up our gear and head for the runway where

I hoped we might catch a flight out. We lucked out. At dusk we were on a plane

back to Samthong. The rest of the trees would have to wait for another day.

Later that evening, sipping from a large tumbler of scotch and

reflecting on the events of the day, I once again asked myself, "How

did I get here and what am I doing in this place?"

The book is 5.5" X 8.5" X 1," has a color soft

cover, is printed in black and white, containing 448 pages, with 105 full

page photos, 11 maps and is priced to sell for $15.00 and 3.00 shipping in the U.S. If you would prefer

to mail a check, send it to: Howard Lewin, 625 35th St. Manhattan Beach, Ca 90266.

Or

Tamarind

Books

Home